When designing a house, first build your giant shed

By Julian Pirie

PHOTOGRAPHS: GERALD SHACKLOCK, JULIAN PIRIE

Capacity is always the issue. My two sheds at home were each at their limit. I had woodwork in one, and a one-off car suffering fabrication right on top of it in another.

When it came time to plan a new house on the new section, I thought of a barn-sized shed. In this barn, I would build all the joinery for the house. But first I had to build the barn.

I had a design that had been kicked around for ages and required a giant leap forward in capacity. This barn, as my workshop, would have good height, tall openings, a range of areas for different tasks and that all-important swing room around the main machine, a multi-function dimension saw.

Like other glimpses I enjoy of bygone eras, I have always loved those English “oak barns” typically housing Aston Martins in magazines portraying classic cars. The vision I had for my barn was of posts and beams and the roof crouching over long flanks, suggesting back rooms filled with the rare and the useful.

16th century

I studied 16th-century original barns, and that led me to decide to build a five-bay, L-shaped “barn” with a square corner room. The whole would be 260 square metres in total. I decided to put posts at 3.8 metre centres, with a cradle of beams catching the rafters at their mid-point. The three-metre-high doors would face the courtyard, and all would be enclosed by 2.4 metre-high, rammed-earth walls around the remaining perimeter.

After the plans and the engineering were worked out, I ordered a load of heavy macrocarpa, mainly 150 mm square for posts and 150 x 225 mm for beams. These things are manageable at one end or the other, but not in the middle. The answer was to build a beam trolley.

This is a very simple design of two trusses with cross-members, wheels and legs. (Good stocks of old galv pipe influences a lot of my designing.) This thing moved all the timber around the site, acted as a bench for all the joinery detailing required, then went on to perform a myriad of tasks, including holding and shifting timber, marble, etc. It still gets loaded up with a stack of 6 x 2-inch (150 x 50 mm) timber whenever machining is needed.

Sky hook

The next challenge was creating a skyhook at, say, six metres up. This “derrick” took little time to make; three lengths of pipe joined by hinge plates on a common apex with a hook. A 12-volt winch mounted on one leg belayed the timber via the apex to haul the beams straight up to the post tops. The prepared ends fitted together, and the derrick was able to waddle, one leg at a time, around the structure to the next beam centre.

It happily hoisted all the beams into place, and has since lifted marble lintels, logs, compressors and most usefully the 300 kg flail mower onto the tractor.

After the post-and-beam assembly, I moved on to the curved braces, all 70 of them, where I routed the ends 50 mm in. I organised a movable platform with a counterweight and a pulley to lift the router and went to work with the extra-large chisel, chips of wood pattering into my face. Three weeks went by as I moved from post to post with a template router and a chisel, then used coach-screws to fasten everything. Well, it sure locked up the whole thing and looked good. So much for the woodwork. The next stage, the rammed-earth walls, was going to be much heavier.

Rammed earth

Rammed earth is a barely moist mix of cement and, in this case, milled sandstone. This mixture is built up into the wall by being compressed between formers in situ. A section of two metres or so goes up 50 mm at a time, to reach a height of 2.4 metres by 300 mm thick by mid-afternoon.

The mixing is important, so I modified a Morrison multi-hoe to run in a trough, with special blades. A job for the determined. Once the mix is thoroughly churned and at the right consistency, it has to be shovelled into a barrow and transferred into the wall cavity. Hard work.

After we had exhausted several helpers, a good team settled down to work through 80 tonnes of the stuff, pillar by pillar, around the perimeter of the barn. Late on a winter’s day with slanting light, the bulky slabs of layered geology cast shadows across our endeavors and Stonehenge wasn’t far away.

To complete the construction I installed a forest of 6 x 2 inch (150 x 50 mm) rafters, and then the whole thing was topped off by about four house-lots of Winstone’s tiles to cover in the roof. The barn instantly aged about 365 years.

Although not on the plans, the barn needed ten large doors to close off the bays facing the courtyard. With each door 2.7 metres tall x 1.8 metres wide, these were always going to be a mission.

Hinges

I fixated on the hinges. Because doors hung left and right between posts, the idea of a common pin holding the hinge plates to each side became irresistible. More galv pipe, some bent flat bar and turned caps all came together as the big hinges. After re-galvanising, they got a faux bronze patina in base coat, then clear coat.

The challenges of constructing the doors prompted me to make a special table 1.8 metres x 2.7 metres. I needed this table initially to weld the rectangular hollow section (RHS) steel into frames; later, of course, it was crucial to hold the big joinery frames for sanding.

The door frames were pre-hung, then fitted out with jambs, sills, tongue-and-groove in-fill and windows. All this in macrocarpa, now finished in Sikkens.

Since the basic build, I have had a full fit-out of the barn, and this has resulted in my now having a working joinery shop, a spray booth, a fabrication area, a gantry gear for handling large frames, a tool lock-up and lots of storage and racking. That one-off car is up one end, awaiting rebirth, and many other projects can inch forward if I live so long.

Rammed earth wall

The courtyard, as part of a larger whole, needed a particular look. On one side, the boundary ran a good length from some gate pillars. This lent itself to a regular run of rammed-earth wall punctuated by little towers.

Here, I used plywood forms to make hollow box-towers, then connected these by three-metre rammed-earth walls. The mix was rammed into a ply-and-angle iron set of forms with through-bolts. Two sets of capping-stone moulds produced big and little tops, which could be cut and fitted with a big diamond blade. This was an experiment in using rammed earth outside, sans roof, and in the time since it has mossed, mellowed and matured, but not washed away.

The overarching concern for the barn as a factory is the joinery I am building for the house. I have graded, dressed and regraded a huge load of pretty scrappy macrocarpa and slowly turned it into windows and doors for the house-to-come. A lucky find of totara went into the French doors, and some redwood has gone into sashes.

House joinery

I also needed some special construction aids for these large items of house joinery. In particular, curved formers in laminated ply, three per side at 1.2 metres x 2.4 metres, inners and outers, on a radius of two metres. These, when stacked and bolted up, will allow me to form a curved section of house wall, something of a central feature in a symmetrical floor plan.

To give this house a period feel, in particular something Italian circa 1550, it was important to give the rammed earth walls some stylistic details. To this end, I made profiled rather than plain end-boards. The end-boards space the formers to give the required wall thickness (here 350 mm) and hold the assemblage to the vertical. I added jointing detail for the connecting pillars and, in the case of doors and windows, a rebate for facing timber.

However, to add a certain feel, I moulded 3 inch x 2 inch (75 x 50 mm) timber into a large S-curve and built up end-boards with this running up the inner and outer edges. When cast into the positive and edging all openings, it should tie in with the jambs. This will shift the appearance of large slabs of wall from brutalist modern to something more classical.

A little bit of alchemy: I decided a stock of polished brass parliament hinges, bought for the French doors, was judged not a good match with other brushed stainless fittings. After I conjured up a vapour of ammonia (easily done, from a bottle) and let the hinges bathe in it in the enclosed spray booth for two weeks, the hinges emerged a bright electric-blue, which eventually mottled to greens and whites. The colours and the hinges are now preserved under two-pot clear urethane. I plan to do some tests to see if I can use a similar trick with the copper spouting.

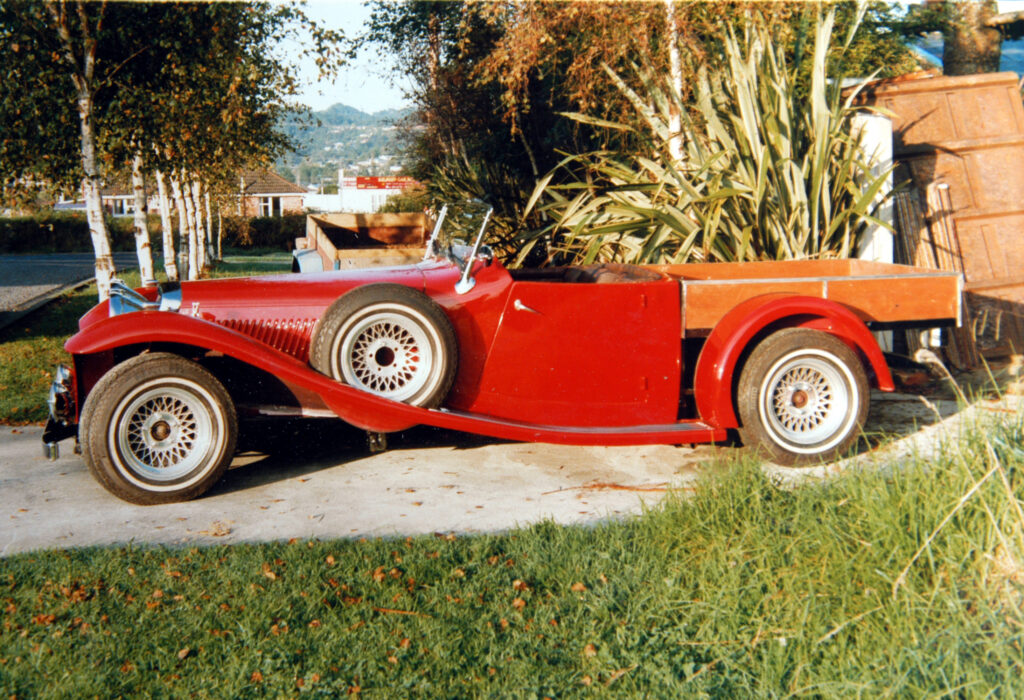

DIY Roadster

The 1930s-style car awaiting restoration is a vehicle that Julian Pirie built himself from “a clean sheet” and used for five years. With nostalgia for the old-style of car with period lights, it is based on two roadsters, the Squire Special (Squire Car Manufacturing Company existed for a few years in the 1930s at Henley-on-Thames in England) and Mercedes 540k. It originally had both tray-back and Tourer configurations. The wooden frame coachwork is made of South Island beech, the chassis is from a Mark VII Jaguar and the rear and now front suspension is from an XJ. The new engine will be a 3-litre straight-six Toyota Supra EFI turbo. For the steel mudguards, Julian Pirie says he took up gas welding at the Manukau Institute of Technology and learned to use an English wheel, to roll, beat, planish and polish the metal himself.