Thousands of hours spent in the workshop have resulted in the creation of some extraordinary working replica scale locomotives

By Sue Allison

Photographs: Juliet Nicholls

“Steam is the only way to go,” says Win Holdaway, a Blenheim-based enthusiast who builds working models from scratch in his backyard shed.

Over the years, Win has spent thousands of hours constructing immaculate scale locomotives, including an 1870s’ Baldwin Standard TE, BR standard class 9F, and a Burrell Special Scenic Showman’s road locomotive. He is currently working on an inch-and-a-half scale 1925 Pennsylvania A5S 040 switcher, complete with tender. “It’s one thing to make a model that looks authentic and another to make it work,” says Win, whose working models can all hold 90-100lb of steam.

Win reckons he spent around 5000 hours building his Burrell Scenic Showman’s road locomotive alone. It is fittingly named Lynette after his wife. While he probably spends more time in his shed than the house, she is his greatest supporter. “It’s more than a hobby. This is his life,” says Lyn, a legal annotator who knows the importance of precision.

“I’m out here most days,” admits Win who, if not in his own workshop, can often be found down at Brayshaw Heritage Park with fellow model engineering enthusiasts.

A love of all things steam

His preoccupation with steam-powered locomotion was inherited from his father. “Ever since I was about 10, I’ve been interested in steam engines,” says Win, who is a joiner by trade. As perhaps the most time-consuming and exacting part of constructing engines is forming the wooden patterns for casting, his joinery skills are invaluable.

Other talents picked up along the way have also stood him in good stead in a craft that involves multiple processes. Win spent time both building and working as an overseer with the Ministry of Works, along the way building his family a home. When the leaky homes revelations meant a change in the building code, he got out and went tool-making. A decade working for a custom jewellery outfit looking after their stamping tools has proved handy when fabricating the fiddlier details of his models.

Burrell Scenic Showman’s road locomotive

Win’s award-winning Burrell Scenic Showman’s road locomotive has featured in Australian and English model engineering magazines and been compared with the 1921 Lord Lascelles, regarded as one of the finest models on the UK rally circuit. The 4-inch model of the early 20th-century English traction engine is about eight feet long, or one-third full-size, and took Win around 5000 hours over six years to build.

“I got a set of drawings out from the UK, but there were quite a few mistakes in them, which was frustrating,” he says. He also realised it was going to be a mammoth task involving making 86 wooden patterns before construction even began.

He started off with the wheels, fitting spokes to the centre castings before attaching rolled rims to the strakes and sending the wheels away to be rubbered. After machining out the front and rear axles, he got to work on the boiler, which was the most complex job.

Win had the barrel plates rolled and welded before forming the tube plates, which involved drilling holes for the 18 tubes to be inserted. Once the firebox and stays had been formed and the tender bolted on, he set to work on the hornplate, rolled and fitted the smokebox, cast the cylinder block, and attached the pistons and rods.

Win undertook all the motion work himself, fabricating the three-speed gears along with the final drive and differential in his workshop. Once the crankshaft and bearings were in place, Win rolled the chimney, finishing it with a brass rim, and attached the gauges and sight glasses.

One job that had Win flummoxed was how to power the canopy lights without losing the authentic look of the locomotive. He mentioned this to his son, Mark, an expert in aviation electronics, who came up with the idea of using two alternators in line, plus an excitor with a little DC motor. Win built a cover complete with rolled brass handles on the sides to make it look like a genuine dynamo. When belted up to the flywheel, it pushes out one-and-a-half horsepower to light up 72 12V bulbs on each side of the canopy.

Win’s joinery skills came into good use when building the canopy. He used European fir in strips, forming the ribs himself. In order to get an authentic paint coat, he got hold of some photographs of Lord Lascelles and matched the colours. He used number 3891 for his little road locomotive, one he didn’t think had been issued by Burrells, and named her Lynette after his wife.

Multidimensional scaling

A head for maths certainly helps as everything has to be scaled in three dimensions, with allowances made for shrinkage in the casting process. Add patience and determination to get things absolutely right, and you have the ideal specifications for a successful model engineer.

“I like to push my own boundaries and not to take shortcuts,” says Win, who spends hours nutting things out. “My father told me that if you don’t know how to do something, make it your business to find out, and don’t let up until you can do it. That’s stayed with me,” he says. “If you go delving around, you can find these things out, but only ask people if you know they know what they’re talking about.”

The internet, he concedes, can be a useful time-waster.

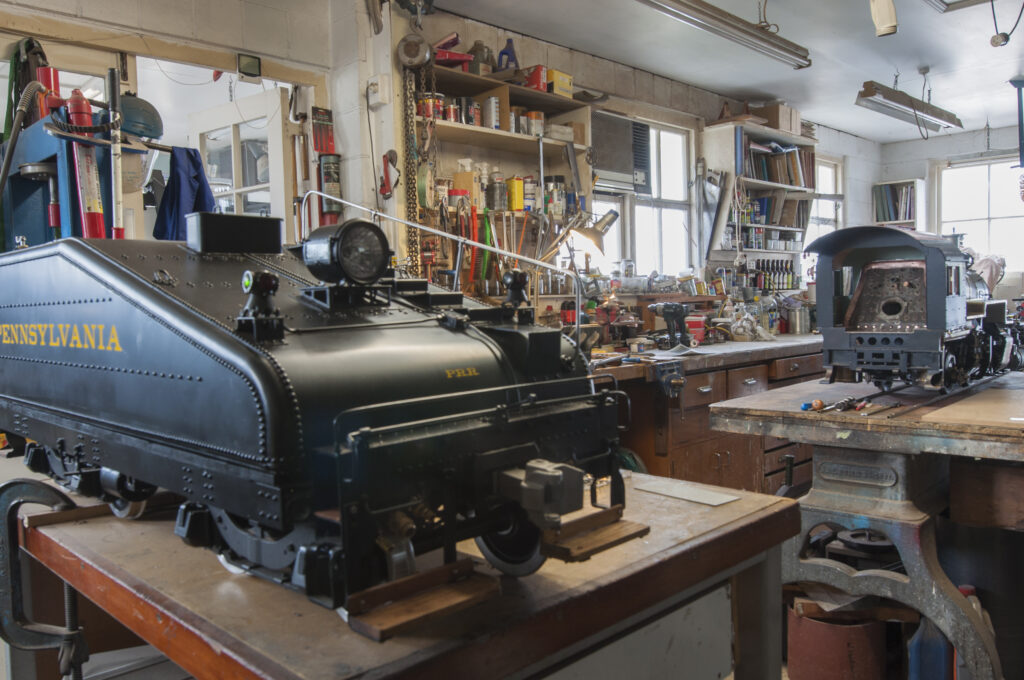

Machining tools in his well-organised workshop include a heavy-duty Colchester metal lathe, small Harrison milling machine, and home-built wood lathe, as well as a comprehensive collection of hand files for fine work and finishing. His “office” alongside houses his computer and drawing board, as well as a pantograph for down-scaling and cutting more intricate components. “It’s especially good for shapes that are hard to file,” says Win.

Real project satisfaction

Win used to have a little coke-fired foundry in his workshop, which he converted to oil after the local gasworks closed down. “The 830 crucible could hold 85lb of metal. When it’s full, it’s something you don’t play around with,” he says. “I ran it for 30 years without having an accident but needed space for bigger machines and lost my nerve at the same time so closed it down.” Luckily he’s got a good friend with a foundry and casting shop in Christchurch, so now takes his patterns there.

Win admits it’s an all-consuming hobby but one that is immensely satisfying when things turn out well. “It keeps you off the streets and out of the pubs,” says the enthusiast who reckons he needs to live another 100 years to finish off his projects. The only certainty is that they will outlast him by a lot longer than that.

Pattern-making

Win’s workshop shelves are packed with wooden patterns, from the tiniest fittings to the huge base for his Pennsylvania A5S tender. Pattern-making is the starting point for building metal models, and the success of the finished engine depends on its accuracy. Win, who built his own wood lathe, uses custom wood as it has no grain to blemish the moulds.

“You can get sets of castings sent out from the UK, but it’s a horrendous price,” says Win, who instead gets hold of the drawings and works it out from there.

“It’s like making a huge 3D jigsaw,” he says. It’s not a simple matter of replicating the final form, as both shrinkage and the negative spaces have to be taken into account. “The metal shrinks when it solidifies so the casting ends up a bit smaller. It’s a shrinkage of an eighth of an inch in a foot, so you’ve got to think it out and do the maths.”

To make the moulds for casting, the custom wood patterns and cores are set in resin sand, with a gating system built in to channel the molten metal. “It can be a bit of a brain-twister, especially getting the negative and positive shapes in the patterns. It’s a painstaking process, especially making cylinders with complex tubing. The pattern doesn’t look anything like the cylinder as it has outside core prints on it,” says Win, who has built about 14 boilers in his time, the biggest for his Burrell traction engine.

“I make all the moulds and cores and fit them together so I don’t hold up the blokes at the foundry,” he says. Once they have been cast, the metal castings are machined and filed to fit. On the bright side, if it all goes wrong, at least you can turn them back to liquid again, he says.

Pennsylvania locomotive (with tender)

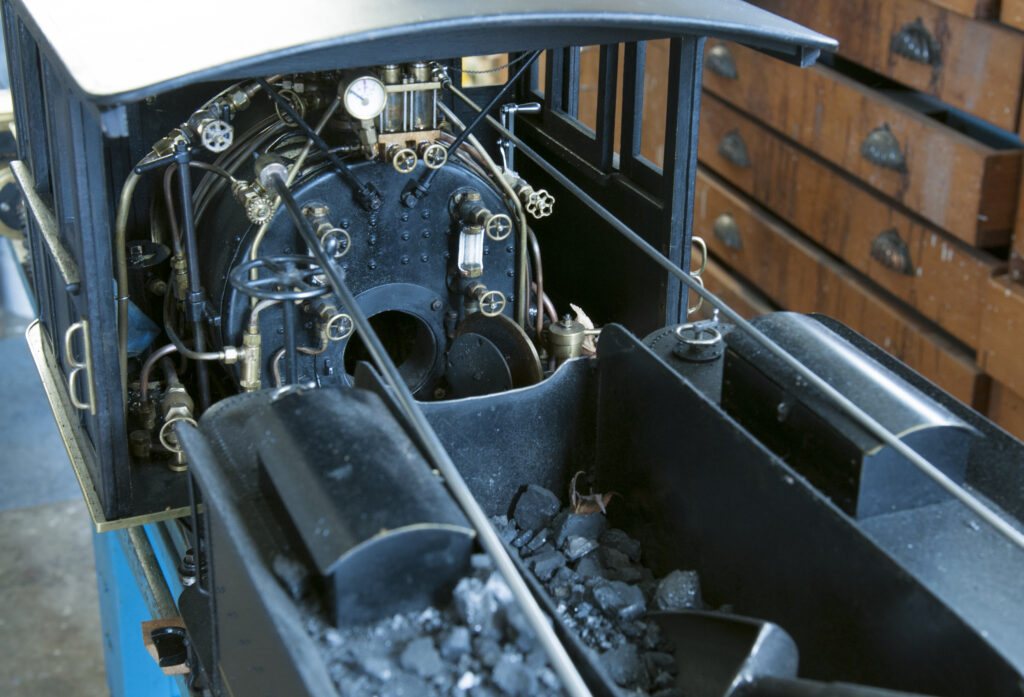

Win is currently working on a Pennsylvania A5S 040 switcher (or shifter), one of the last five engines built by the Pennsylvania Railroad in 1925. Win’s working model is an inch-and-a-half-inch scale built to operate on a 7¼-inch ground level track. He has already completed the tender, which sits behind the locomotive and is designed to carry water or coal. The tender alone took him more than a year to build.

The locomotive, held together with 2500 rivets, is made out of steel, aluminium, copper, and brass. Win used imported cartridge brass to roll the firebox, as normal brass would crack. He made the crankshaft out of a hulking piece of 4140 high-tensile steel, six inches round and 28 inches high, lathing it down from each end as it was too heavy to lift off the floor. At the other end of the scale, he hand-filed the small bronze bell after forming the outer shape on his lathe, and used a regular cross-hatch wood file to imprint the tread on the step.

Baldwin Standard TE

Win’s Baldwin Standard TE locomotive is a live steam miniature built to operate on 5-inch gauge tracks. NZ Railways imported six of these small engines in 1879 from Philadelphia before domestic production began in Christchurch’s Addington workshops in the late 1880s. “I managed to get some drawings from a chap in Toronto who worked for the railway,” says Win, who constructed it to the scale of 1.428 inches. Scaling it down presented major challenges, particularly the construction of the boiler. “I like challenges,” says Win, who never counts his hours but reckons the locomotive would have taken him well over 2000 hours over 18 years.