From racing to making, Craig Greenwood has met the challenge

By Jude Woodside

Photographs: Jude Woodside

Craig Greenwood is one of the best examples of someone who turned his passion into a business. He is also one of New Zealand’s most prolific racing car builders.

Craig got into motor racing in the early 1990s, progressing from competitive kart racing to Formula Vee (now Formula First). The class is based on a 1200 cc VW motor and uses a collection of stock parts to form a competitive car from the engine, transmission, front suspension, brakes and wheels built into a space frame.

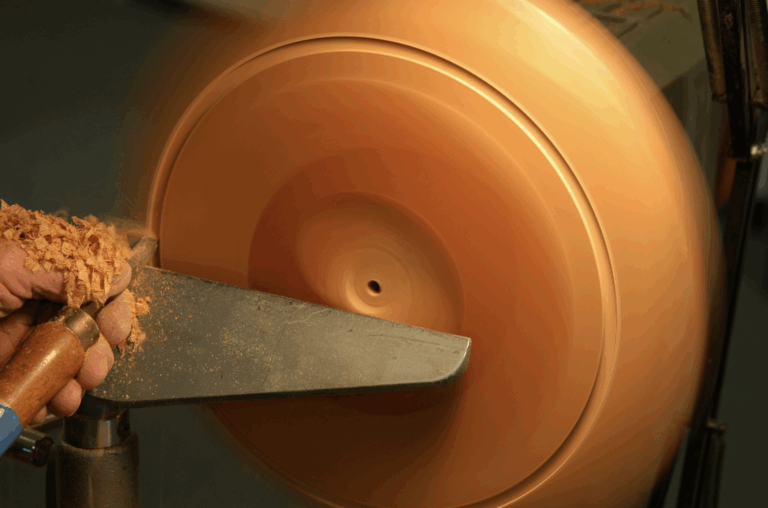

The body is fibreglass or carbon fibre. It’s a racing class that allows an enthusiast to build and maintain their own car. Craig bought his first car but soon decided to build his own, working nights and weekends in a cramped single garage with little more than an oxy-acetylene welder, a hacksaw and a hand-held drill.

“I wasn’t all that successful at first. Of 18 starts I made, I only finished four,” says Craig.

“I realised that just knowing how to weld a chassis wasn’t enough, so I started to read about designing and building race cars.”

Competitive

The cars got better, and he started becoming competitive. He realised it was more productive to build multiple cars and race them as a team. By 1993, with three cars, Greenwood started a scholarship system to find other drivers for his team. He was by now becoming competitive in the class. Before long, he had a team of six and was one of the biggest racing teams in the competition.

Craig went on to win the New Zealand Formula Vee Championship in 1997, and his team won in 1998 and 1999. Craig has built 23 Formula Firsts and developed a reputation for building quick and reliable cars, most of which are still racing.

By 1999, Craig had come up with a new design. Based on the Formula First series and with the knowledge earned from running his own team, he knew the drawbacks in the current design.

Motorcycle engine

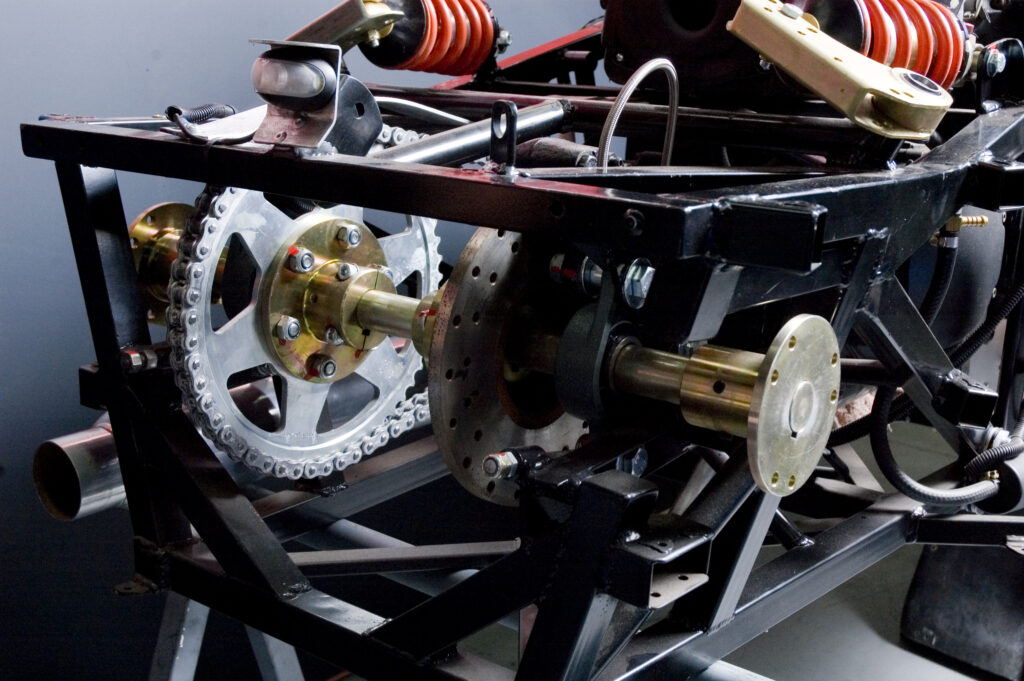

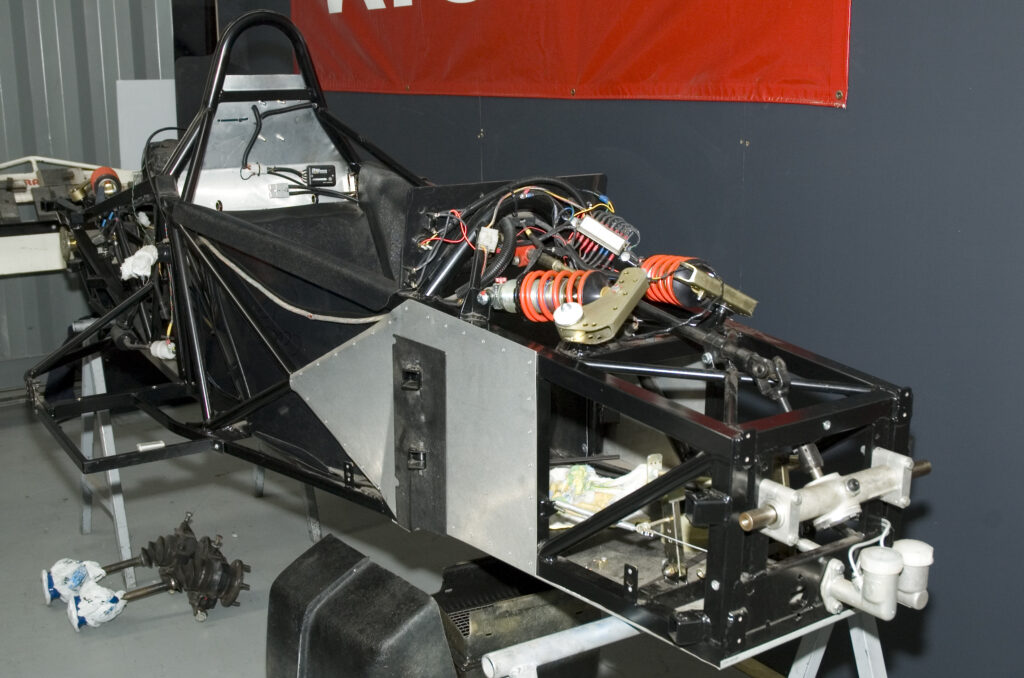

“I realised I could build a car from a space frame and a motorcycle engine. I wanted to make it simple. The car needed to have easy access to replace or work on the motor, it needed to have easily replaceable parts, and above all, it needed to look and sound like a racing car. So we designed the body to look like a ’99 Ferrari.”

Craig wanted to go beyond simply owning the team, he started a new series—Formula Challenge. With that, he also pioneered the “arrive-and-drive” concept, where drivers could lease cars or simply rent the car for the race. All the cars were set up to be identical; the only variable should be the skill of the driver. This was intended to be a driver’s championship. He also ran a scholarship program to encourage new talent.

By 2002, the series had won recognition on TV with a winter series. The series ran to 2005.

Formula Challenge Racing now concentrates on providing individuals with the thrill of piloting a car that looks, sounds and handles like the real thing. It has a base at Taupo raceway but is also available at Hampton Downs and now at Rua Puna. They run 12 open-wheeler Formula Challenge cars and nine Vs, both Ford and Holden, to cater to all tastes.

The Challenge car has changed little; the power plant is a Suzuki GSXR 1100 cc motorcycle engine. The car sports wings, spoilers and a demountable nose section which has a safety element. In any impact, the nose section helps to absorb damage without distorting the chassis or suspension.

The suspension is hard in typical race-car style, and the steering is positive and responsive. The sequential five-speed gearbox is controlled with two buttons on a demountable steering wheel.

The car generates an impressive 150 brake horsepower with a top speed of 230 km/h. It is capable of 0-100 km/h in 3.8 secs. It can generate a force of nearly 2Gs on corners, and at a maximum of only 40 mm off the ground, the driver has a sense that the speed is electrifying.

Before heading off for a few laps, drivers see a video of a track drive. The cars are linked to a datalogger so the team can analyse each lap with the drivers to highlight good and bad practices to help drivers fine tune their skills.